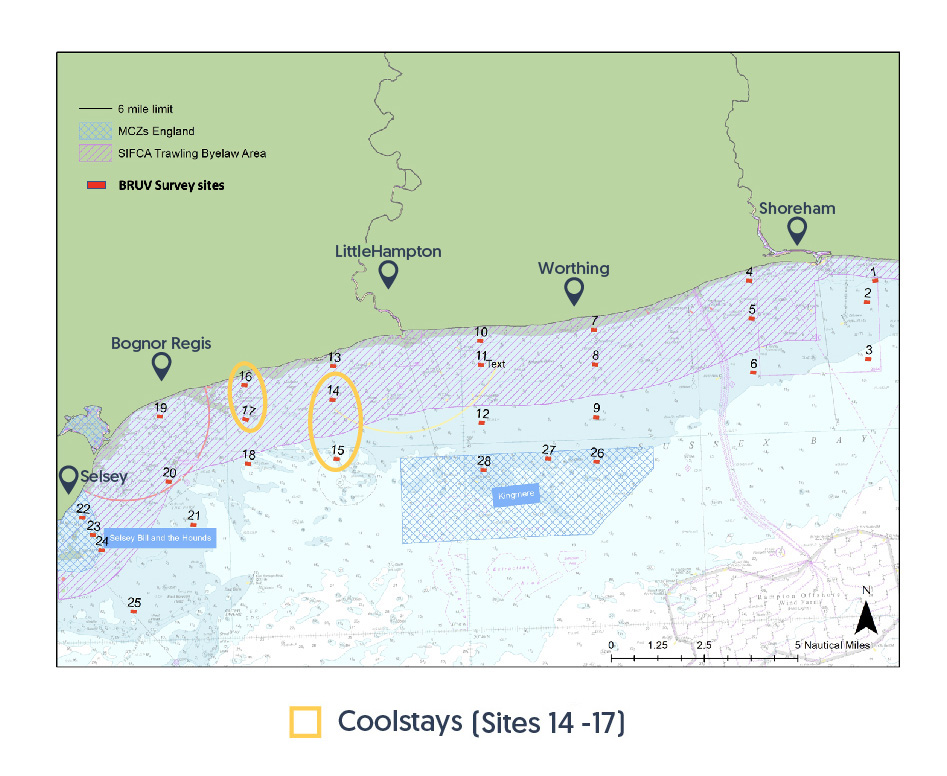

Coolstays supported 4 kelp survey sites along the Sussex coastline in 2022

Coolstays supported 4 survey sites in partnership with GreenTheUK and Blue Marine. The survey work was a collaborative study between Blue Marine Foundation and University of Sussex as part of the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project.

Sites 14 to 17 were supported by Coolstays.

Key Findings from the Baited Remote Underwater Video Survey 2021 & 2022

The waters off the Sussex coast historically supported dense kelp beds of mixed seaweed with at least six different species of kelps and other large brown macroalgae. To help protect essential fish habitats and remove one of the key barriers to kelp recovery, the Byelaw excludes trawling in the area to give kelp a chance to recover. The Sussex Kelp Recovery Project (SKRP) was launched to support and enable the natural restoration of kelp and essential seabed habitats in the Nearshore Trawling Byelaw area.

One of the aims of the SKRP is to understand the ecological, social and economic value of kelp and the Sussex IFCA Nearshore Trawling Byelaw. This will allow benefits from the byelaw and associated impacts to be evaluated and quantified. This programme is undertaken in collaboration with research organisations, regulators, fishermen, conservation groups, marine user groups and local communities.

Annual monitoring aims to record any changes in species diversity and composition following introduction of the Sussex Nearshore Trawling Byelaw and the anticipated recovery of kelp habitat. This will inform a better understanding of the trajectory of ecosystem recovery and the value to biodiversity of the Nearshore Trawling Byelaw.

In 2021 and 2022, the University of Sussex with support from Blue Marine deployed Baited Remote Underwater Videos at 28 sites along the Sussex coast to assess diversity and abundance of mobile and benthic-associated species within and outside the Nearshore Trawling Byelaw area.

Key findings:

The species richness between 2021 and 2022 was not significantly different, but the lower number of invertebrates identified in 2022, is potentially linked with increased algal cover which obscured benthic-associated invertebrates.

Sussex sites from both years are similar in species composition and are structured by the environmental variables macroalgae percentage cover, year and depth. There is a clear difference between the position of the 2021 sites and 2022 sites, suggesting that the species composition has shifted.

Methodology:

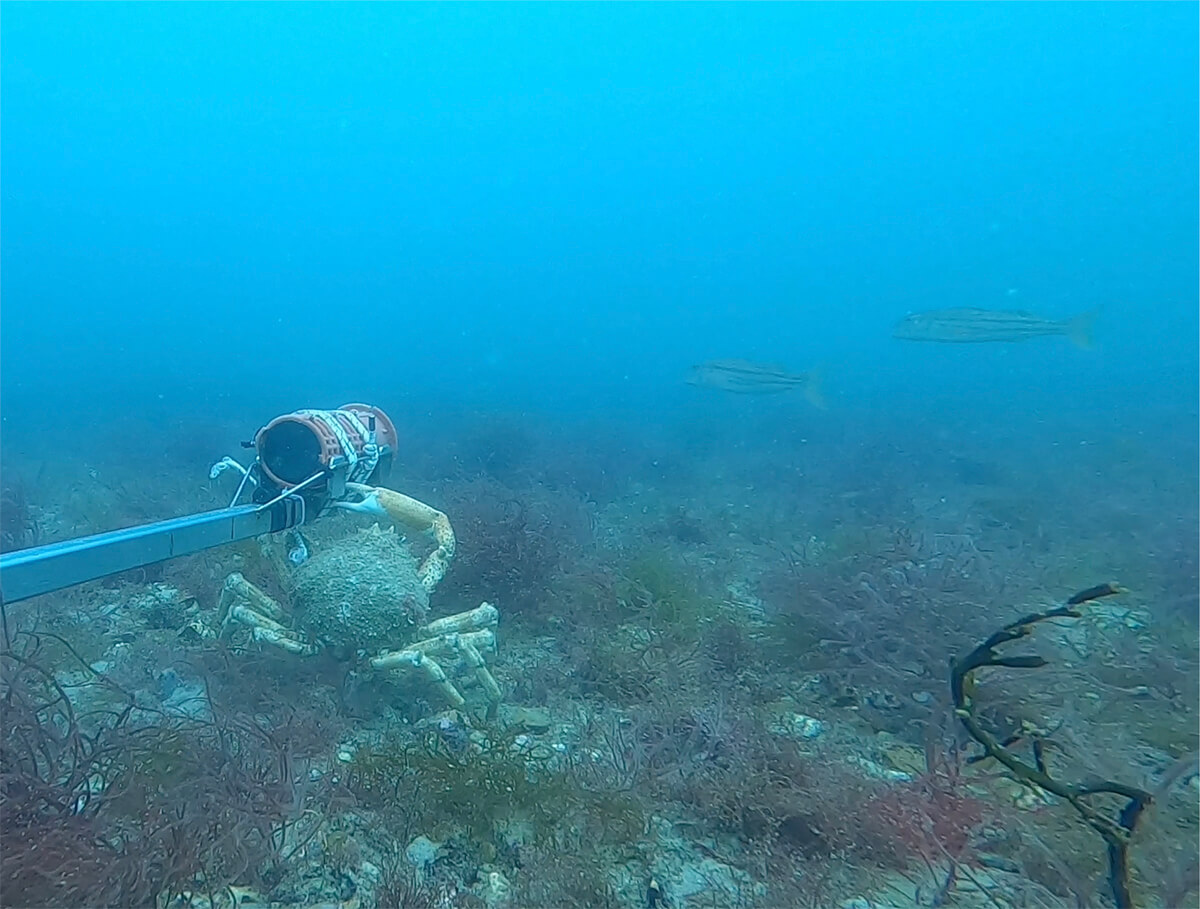

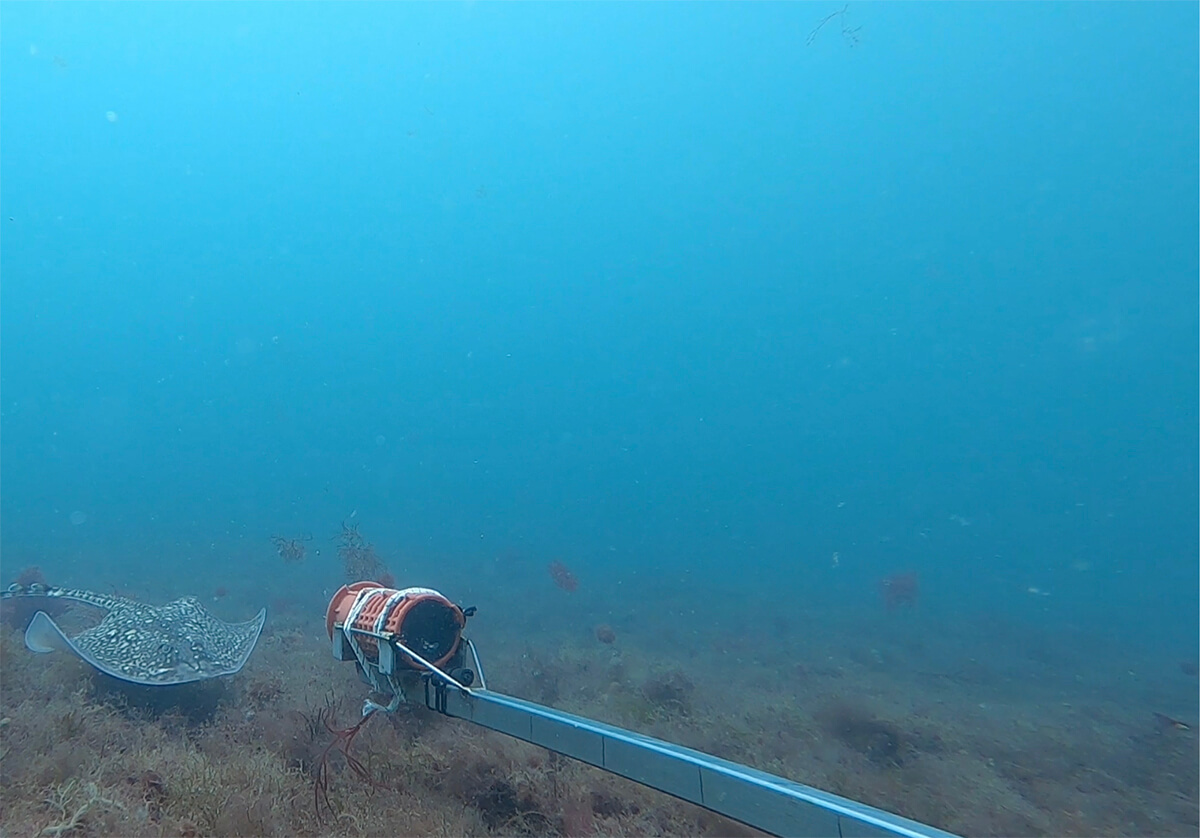

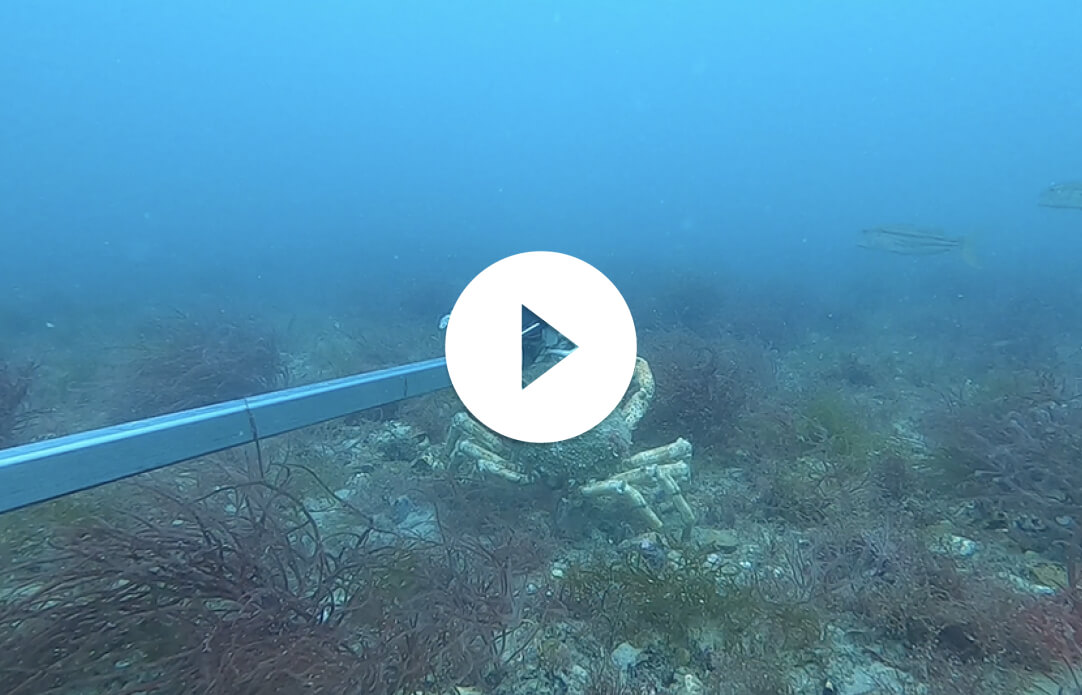

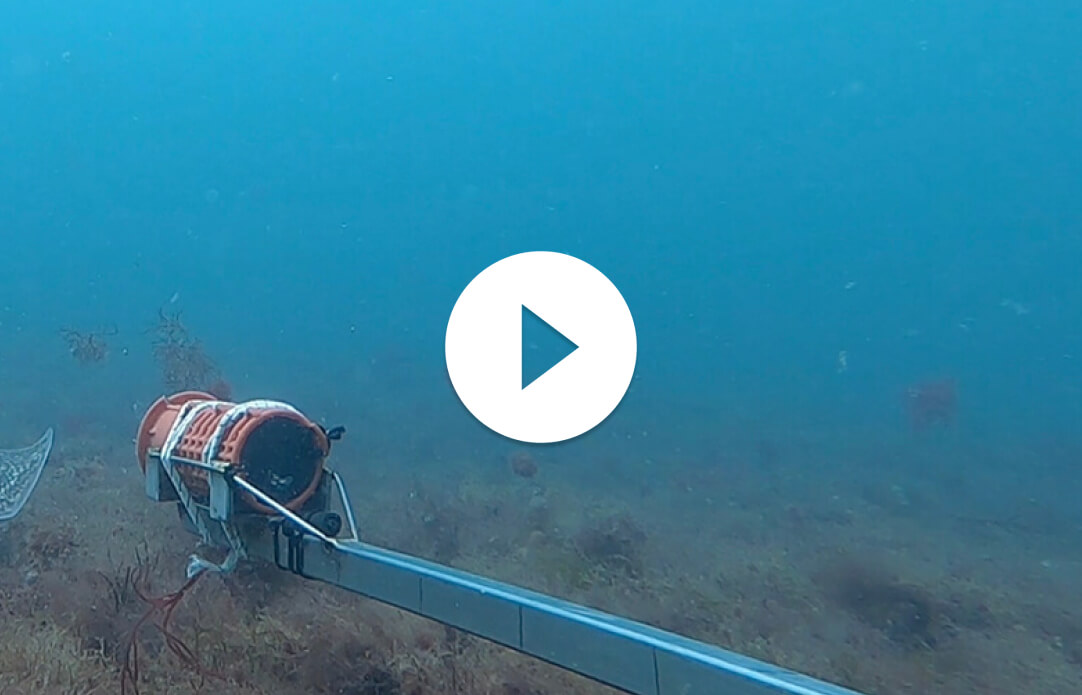

The methodology used to assess diversity and abundance of mobile and benthic-associated species is a Baited Remote Underwater Video System (BRUVS), which is used to collect quantitative data on mobile organisms in different experimental treatments.

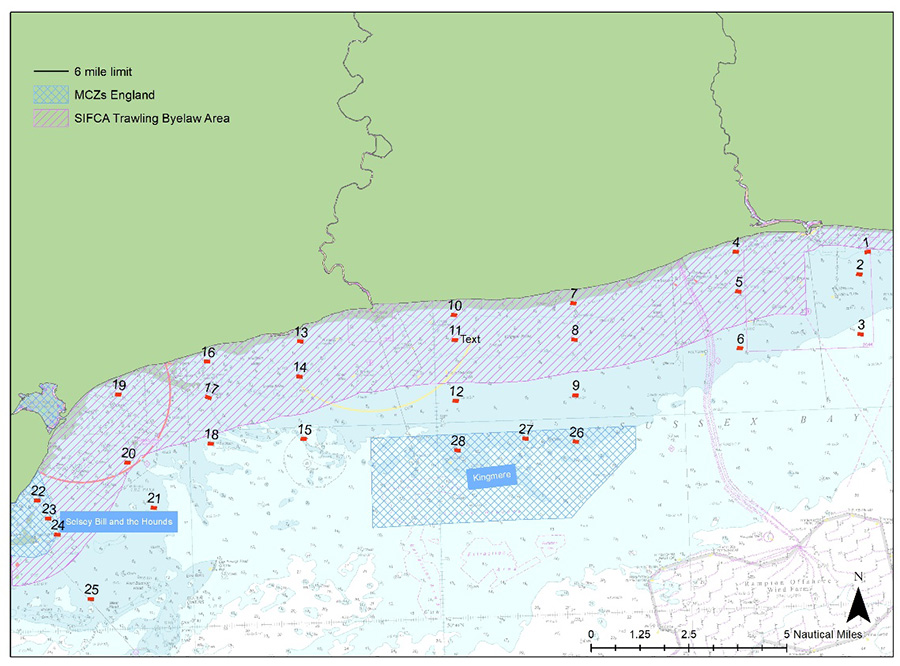

In July 2021 and July 2022, the University of Sussex team deployed stereo Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUVs) in 28 different locations along the coast of Sussex (Figure 1).

There are three treatments:

- Nearshore Trawling Byelaw - areas inside the designated byelaw closure, where previous dense kelp beds were present;

- MCZ – the Kingmere and Selsey Bill Marine Conservation Zones; and

- Open Control – areas outside the Byelaw area and MCZs.

Figure 1: Map of the 28 sites along the Sussex Coast that were sampled with BRUVs in July 2021 and July 2022.

Figure 1: Map of the 28 sites along the Sussex Coast that were sampled with BRUVs in July 2021 and July 2022. The sites were selected to match towed transect videos deployed by Sussex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (IFCA) to provide faunal datasets that complement their habitat data. An extra deployment of the BRUVs at one site in Swanage in 2021 and in Pullar Bank in 2022 provides further comparative information with kelp dominated ecosystems.

BRUVs were equipped with 3 GoPro HERO 8 cameras (Figure 2). The bait canister of the BRUVs was filled with one semi-thawed and one frozen scad (Trachurus trachurus), which were sliced into 4 different pieces to enhance the strength of their scent. At each site, three different BRUVs were deployed 150 m from one another, for 65-70 min before being retrieved and the footage downloaded. For each BRUV deployment the following measurements were taken; GPS (Latitude and Longitude), date, time of deployment and depth (based on sonar).

The videos were subsequently reviewed to record the species observed (scientific name/common name), the time observed in the video, the number of individuals and the duration of observation.

The maximum number of individuals on screen (MaxN) for each species recorded at each site was used in data analysis. MaxN is considered a conservative estimate of relative abundance, eliminating the chance of counting the same individual multiple times.

Statistical analyses explored Abundance, Species Richness and Effective Number of Species (ENS) between treatment areas.

Figure 2: BRUV structure, including the two stereo GoPro Hero 8 cameras (A, B), the third GoPro Hero 8 camera set to time lapse for habitat (C) and the bait canister (D).

Figure 2: BRUV structure, including the two stereo GoPro Hero 8 cameras (A, B), the third GoPro Hero 8 camera set to time lapse for habitat (C) and the bait canister (D). Preliminary Results for 2021 and 2022

Diversity

From the 28 survey sites (excluding kelp control habitats in Swanage and Pullar Banks) a total of 49 vertebrate and invertebrate species were identified from the BRUV footage in 2021. Of these, 25 were vertebrates and 24 were invertebrates.

In 2022, a total of 36 vertebrates and invertebrates were identified, of which 22 were vertebrates and 14 were invertebrates.

Of the vertebrate species identified over the two years:

- 19 vertebrate species were seen both years;

- 6 vertebrate species were identified in 2021 but not in 2022: Yarrell’s blenny (Chirolophis ascanii), Tub gurnard (Chelidonichthys lucerna), Cuckoo wrasse (Labrus mixtus), Shanny (Lipophrys pholis), Thornback ray (Raja clavata), Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scomber); and

- 3 vertebrate species were identified in 2022 but not detected in 2021: Common stingray (Dasyatis pastinaca), Grey gurnard (Eutrigla gurnadus), Sand goby (Pomatoschistus minutus).

Of the invertebrate species identified over the two years:

- 12 invertebrate species were detected in both years;

- 12 invertebrate species were identified in 2021 but not seen in 2022: Brittle star (Amphipholis squamata), Spotted sea hare (Aplysia puncata), Ocean quahog (Arctica islandica), European painted top shell (Calliostoma zizyphinum), Hermit crab (Diogenes pugilator), Sea slug (Doris pseudoargus), Squat lobsters (Galathea squamifera), Angular crab (Goneplax rhomboides), Great spider crab (Hyas Araneus), Dog whelk (Nucella lapillus), Common prawn (Palaemon serratus) Netted dog whelk (Tritia reticulata); and

- 2 invertebrate species were seen in 2022 but not detected in 2021: Masked crab (Corystes cassivelaunus) and Bittersweet clams (Glycymeris glycymeris).

Overall more species were identified in 2021, especially invertebrate species. There are a few explanations as to why this could be. In 2022, the macroalgae coverage was a lot higher which made species identification much more difficult as many invertebrates were covered by seaweed and thus, undetectable on the BRUVs. In addition, seaweed transported by tidal currents often blocked views from the cameras.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Professor Mika Peck, Valentina Scarponi, Alice Clark, Grace Etherington and Masters students at University of Sussex for undertaking surveys, data analysis, reporting and collation of images and footage.

Thanks to all GreenTheUK sponsors and Barclays Plc for support of the Blue Marine Foundations Sussex research programme.

This case study was adapted from a report published in December 2022: A collaborative study between Blue Marine Foundation and University of Sussex as part of the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project. The report authors were Sam Fanshawe of Blue Marine Foundation and Alice Clark, Mika Peck and Valentina Scarponi from the University of Sussex, School of Life Sciences, Ecology and Evolution.

UN's Sustainable Development Goals

As a GreenTheUK partner, you support projects that are in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.